By Wietse Coppes

In the years 1916-1918 Mondrian produced two self-portraits. For a long time it was thought that these had both been commissioned by his friend, collector Sal Slijper. However, the research into the letters Mondrian wrote to Slijper shows these works in a surprisingly new light. They reveal the reason why during this period Mondrian decided to make self-portraits. Both of these ended up at the Kunstmuseum The Hague, but one of these made wanderings that remained obscure until now.

Provenance details in catalogue raisonné

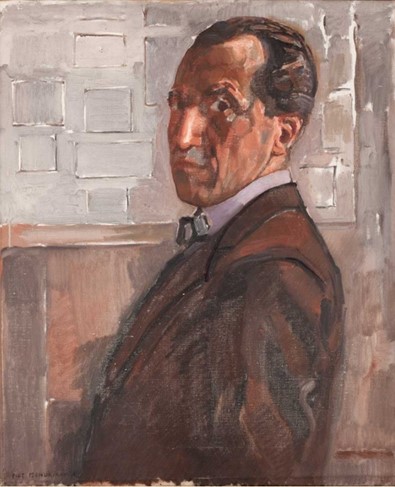

In the category ‘Late Naturalistic Works’ in Piet Mondrian: catalogue raisonné (1998), a drawn self-portrait from 1916 is included under number C21.[fig. 1] In the entry a passage is printed from a letter Mondrian wrote to Slijper, dated 4 January 1916: ‘I am finally about to get some work done here: the self-portrait included.’ The provenance details state that the work came into Slijper’s possession at some unknown point in time. Following Sal Slijper’s death in 1971, it – together with almost 300 other works by Mondrian in his possession – was bequeathed to the Haags Gemeentemuseum (now Kunstmuseum The Hague).

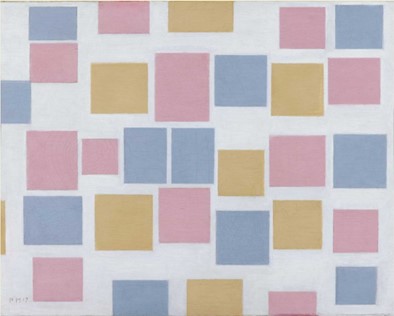

Mondrian’s painted Self-portrait from 1918 is included in the above-mentioned oeuvre catalogue under number C23. [fig.2] With this entry no letters are mentioned. As provenance it states 1918-1971: S.B. Slijper, Blaricum, and then, also as part of the Slijper bequest, Kunstmuseum The Hague. In the collection catalogue Mondriaan in het Gemeentemuseum Den Haag (2008), compiled by Hans Janssen, the museum’s curator at that time, additional information is provided which confirms the assumed acquisition by Slijper in 1918: ‘Slijper commissioned Self-portrait in 1917-1918, when he resolved to collect several works by the artist.’ The author does not provide a source for this information.

A self-portrait for a suit

While annotating the letters Mondrian sent to his friend and patron Slijper, the team of The Mondrian Papers found new information on both self-portraits. Sal Slijper indeed seems to have been the one who gave Mondrian the idea to create a self-portrait. As the artist wrote to the collector on 2 April 1916: ‘Now that people are going to promote me like this, I too am starting to think it necessary to put a portrait out into the world!!’ With ‘promote’ Mondrian was referring to the support he was then starting to receive from renowned art educator H.P. Bremmer. Not long before, the latter had approached Mondrian and proposed paying the painter a monthly sum of 50 guilders, in exchange for four middle-sized paintings a year. Mondrian regarded this allowance as a recognition of the legitimacy of his search. That this prompted Mondrian to make a second self-portrait, illustrates the importance of Bremmer’s gesture. Traditionally, the self-portrait was seen as a means to connect the image of the artist to their work. (What Mondrian was unaware of was that the idea for this allowance came from the critic Willem Steenhoff, as discussed in an earlier post.)

Mondrian probably first started work on a self-portrait for Slijper as a token of his appreciation for the latter’s friendship. This, however, was not the painted self-portrait, but the aforementioned self-portrait in charcoal on paper. With a size of 121×63 centimetres it is quite a substantial drawing, as well as being the only self-portrait from 1916. In another letter to Slijper, also from 1916, Mondrian writes: ‘You can have the self-portrait in exchange for the suit.’ This proves conclusively that the drawing came into Slijper’s possession that year. It also becomes clear that this does not refer to the painted self-portrait, which, after all, was dated by Mondrian ‘1918’.

Mondrian may have started on that work in 1917, or even possibly as late as 1918. This hybrid work may be painted in a naturalistic style, but in the background it includes a reference to Mondrian’s abstract work at the time. It was painted in a small hut in the countryside between Laren and Blaricum that Mondrian used as a studio. Wooden paneling up to shoulder height can be discerned in the background. Above that cardboard rectangles appear to have been mounted on the wall using drawing pins. This way of working was entirely in line with Mondrian’s style in 1917, when he was painting rectangles in primary colors on a white foundation without ‘fixing’ them with black lines.[fig. 3]

From Mondrian, through Maris, to Slijper

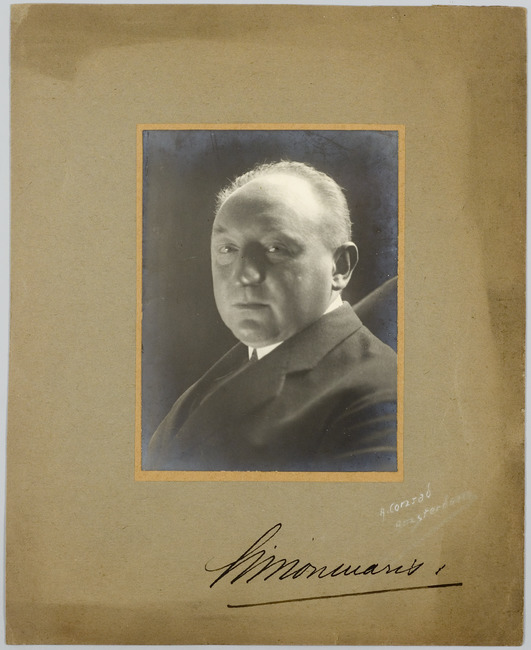

Mondrian brought the painted self-portrait to Paris, where he returned at the end of June, 1919. It was one of the few works he took with him from the Netherlands. All of the paintings and drawings he had left behind in Paris in 1914, he sold to Slijper in one blind purchase. The fact that he kept the self-portrait for himself says something about the importance Mondrian attached to it. Not until mid-1920, when he found himself in financial difficulties, did he decide to sell the work to the ever-interested Slijper. On 3 August 1920 he wrote to him: ‘[Simon] Maris has gone back [to the Netherlands]. He has that painted self-portrait of me on the condition that you can purchase it. Because I said that I had more or less promised it to you.’ [fig. 4] Some weeks later another letter from Mondrian arrived. From this it appears that Maris – who had taken work from his friend Mondrian in consignment before – played a part in the provenance history of this work beyond merely that of courier. Slijper appears to have paid Maris 500 francs (now approximately € 425) for the portrait. Mondrian furtively explains how the deal involving the self-portrait came about.

‘Here’s what happened. In a moment of confidentiality Maris said that Paris was kind of fun after all. Then I said “yes, if only I earned a bit more”. Then he said “let me give you 1000 francs [now approximately € 850], we’ll sort it out”. That was really decent of him, but I couldn’t accept it because he might not want to have any of my new work. Then he said “let me give you 500 then, then you can give me a small study yourself”. That I did accept. When he returned from Switzerland I felt a bit conscience-stricken, so I brought him the portrait since he had enquired after its price earlier, which at the time I didn’t give him because I’d said that I had more or less promised it to you. But as I didn’t have anything else, I brought him the portrait anyway on the condition that you could purchase it. Maris then said “I only meant a modest study”, but I was glad it had been settled and now that you have given him the 500 [francs] everything is alright, just as if you had bought it from me. It’s not too expensive I think, Beekman, among others, at the time said that I had asked you ƒ 200 [now approximately € 1.100] for it, but to me that seemed like too much for you.’

In this rather roundabout way, in August 1920 the work finally came into possession of Sal Slijper. The self-portrait must nevertheless have been a welcome acquisition, because it meant the collector was now in possession of a prestigious painted self-portrait from the most prominent artist from his collection.