by Wietse Coppes

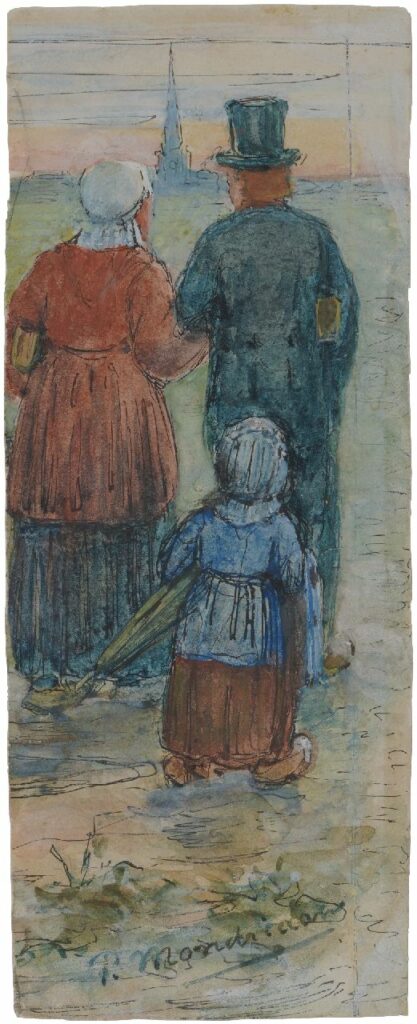

In the spring of 2018, former curator of the Kunstmuseum Den Haag Hans Janssen discovered a small, previously unknown watercolor by Mondrian (fig. 1). Its left half was found to be missing, but the small work could nevertheless be related to two other surviving watercolors, which have strong similarities in size, subject matter, execution and signature (figs. 2 & 3). The two already known works are included in Piet Mondrian: catalogue raisonné with a tentative dating of c. 1898-1901. However, a fresh look at the group of three works yields a new hypothesis, linking the watercolors to Mondrian’s apprenticeship with retired painter and draftsman Jan Braet von Uberfeldt in the years 1888-1892. This places them among his earliest surviving works.

Mondrian’s first teacher

When Mondrian applied to Queen Regent Emma for assistance with his study expenses at the end of February 1892, he reported that he had been trying to become proficient in painting “for four years” through self-study. The two certificates of proficiency in drawing he obtained in 1889 and 1892, respectively, exempted him from taking the entrance exam for the Rijksakademie voor Beeldende Kunsten, where he began his training as a free artist in the fall of 1892. In his preparations for obtaining both certificates, Mondrian was assisted by retired drawing teacher Jan Braet von Ueberfeldt (1807-1894). Braet had been trained by Jan Adam Kruseman and had specialized in depicting Dutch costumes, for which he traveled throughout the country. By the end of his career he had settled in Doetinchem, a short distance from Winterswijk where the Mondrian family settled in 1880. How Mondrian and Braet came into contact cannot be traced.(1) It can be said, however, that Braet must have been happy with the progress of his talented pupil. This appears from the fact that he wrote an attestation (which has unfortunately not survived) for Mondrian on behalf of his aforementioned request to Queen Regent Emma (letter 0001, dated February 27, 1892), as well as from the fact that Braet provided Mondrian with financial support so that he could settle in Amsterdam.(2) Thus Braet made an important contribution to the young artist’s early career.

Dutch Costumes. Drawn after Nature

Jan Braet von Ueberfeldt is best known for the lithographs of Dutch costumes he produced in close collaboration with his friend and colleague Valentijn Bing (1812-1895). These lithographs were produced from watercolors that Braet and Bing made “after life,” and were published by art dealer Frans Buffa & Zonen. Braet and Bing traveled throughout the Netherlands in the mid-19th century to study and record the various costumes. Still today, their watercolors and widely distributed lithographs are an important source for research on Dutch costumes. A selection of the plates appeared in 1857 in the book Nederlandsche Kleederdragten. Naar de natuur geteekend (Dutch Costumes. Drawn after Nature). Reprints of this standard work appeared in 1976 and 1978. The last reissue made use of the original watercolors, making this edition the closest to the original works by Braet and Bing.

Entries in Piet Mondrian: catalogue raisonné

Mondrian’s two already known watercolors from the series of three were dated by Mondrian expert Robert Welsh in Piet Mondrian: catalogue raisonné with a tentative dating of c. 1898-1901. In the commentary to both works he wrote: “these two gouaches are impossible to assign a date with any certainty.”(3) Welsh raises the possibility that these are designs for tiles, but could just as easily be “independent works of art.” He did not make the link with Mondrian’s early teacher Braet von Uberfeldt, in whose oeuvre such works are by no means exceptional. The somewhat clumsy rendering of the figures and the not so fluent technical execution also argue for an earlier date than the one given by Welsh. The works are devoid of the flowing lines one might expect from an artist who has completed his studies at the Rijksakademie (as was the case with Mondrian in 1897), but rather bear witness to the unsteady hand of a novice.

Striking similarities

All three works show typical Dutch scenes. On the two works Welsh knew and described, he identified local costumes from the island of Marken and Zuid-Beveland. Inquiries at the Nederlands Openlucht Museum (Dutch Open Air Museum), however, reveal that Mondrian – unlike Braet and Bing – allowed himself the necessary liberties in his rendering of the supposed costumes.(4) Partly because half of the newly discovered work is missing, it is difficult to recognize a specific costume and thus a region. It seems quite conceivable that Braet had Mondrian produce pastiches after his own watercolors and preliminary studies of Dutch costumes as a study assignment. Braet must have had several examples of these in his possession, so it would have been a logical teaching assignment for him to provide to the young Mondrian. A comparison with several lithographs by Bing/Braet reveals some striking similarities. For example we see similar compositions, corresponding headgear, the frequent appearance of the Dutch flag, and the same staging. For example, Bing/Braet’s depiction of the costume from Marken (fig. 4), like the Mondrian identified by Welsh as Marken (fig. 2), was set in a wintry landscape. This does not seem to have been a coincidence, but a deliberate choice. It is almost as if Mondrian attempted to show the figures depicted frontally by his teacher from behind. If we compare the face of the skating child on the right with the faces on Bing/Braet’s lithographs, it is striking how much better the master’s works are at that time, which again contributes to the suspicion that Mondrian was still at the beginning of his career while making them.

Revised dating

For the reasons described above, the three works will be included in the digital RKD’s digital Piet Mondrian oeuvre catalog with the revised dating of c. 1888-1892. This makes them examples of Mondrian’s earliest work, of which very little has survived. With regards to Mondrian’s study work there is even next to nothing that has been handed down. The watercolors contribute to our knowledge about the period of self-study that preceded Mondrian’s education at the Rijksakademie voor Beeldende Kunsten, and could therefore yield new insights regarding his first steps as an artist.

Notes

(1) In his book on Mondrian, author Jan Stap writes that Frits Mondrian introduced his nephew Piet to Jan Braet von Uberfeldt, whom he supposedly knew from Amsterdam. However, he provides no further evidence for this. Jan Stap, Piet Mondriaan (1872-1994). De mens achter de schilder, Erfgoedcentrum Achterhoek en Liemers 2001, pp. 22-23.

(2) Shortly after Mondrian’s death on Feb. 1, 1944, an interview with the painter by Jay Bradley appeared in the Knickerbocker Weekly. In it, Mondrian revealed that “another man paid for my studies for three years, sending me at 19 to the Amsterdam Academy of Fine Arts.” It is generally assumed that this refers to Braet von Uberfeldt (CRI, pp. 114-115).

(3) Joop Joosten & Robert Welsh, Piet Mondrian: catalogue raisonné, Blaricum 1998, Part I, p. 210.

(4) Message from curator Jacco Hooikamer of the Dutch Open Air Museum to the author, dated Nov. 12, 2023.