by Clarissa Frascadore

In 1956 Michel Seuphor published the first and widely cited biography of Piet Mondrian. In it he described the artist as an ascetic, a saint and a hermit. Time and again scholarly publications have elaborated on this description until, in our time, it has become the myth of Mondrian. Piet Mondrian was later defined in a psychological article as ‘a rigid, isolated, compulsive character, sternly defended against nature and human movement.’ The myth is challenged, however, by Mondrian’s letters and by a re-evaluation of his use of photography for self-representation.

Mondrian’s letter to Mies Elout-Drabbe

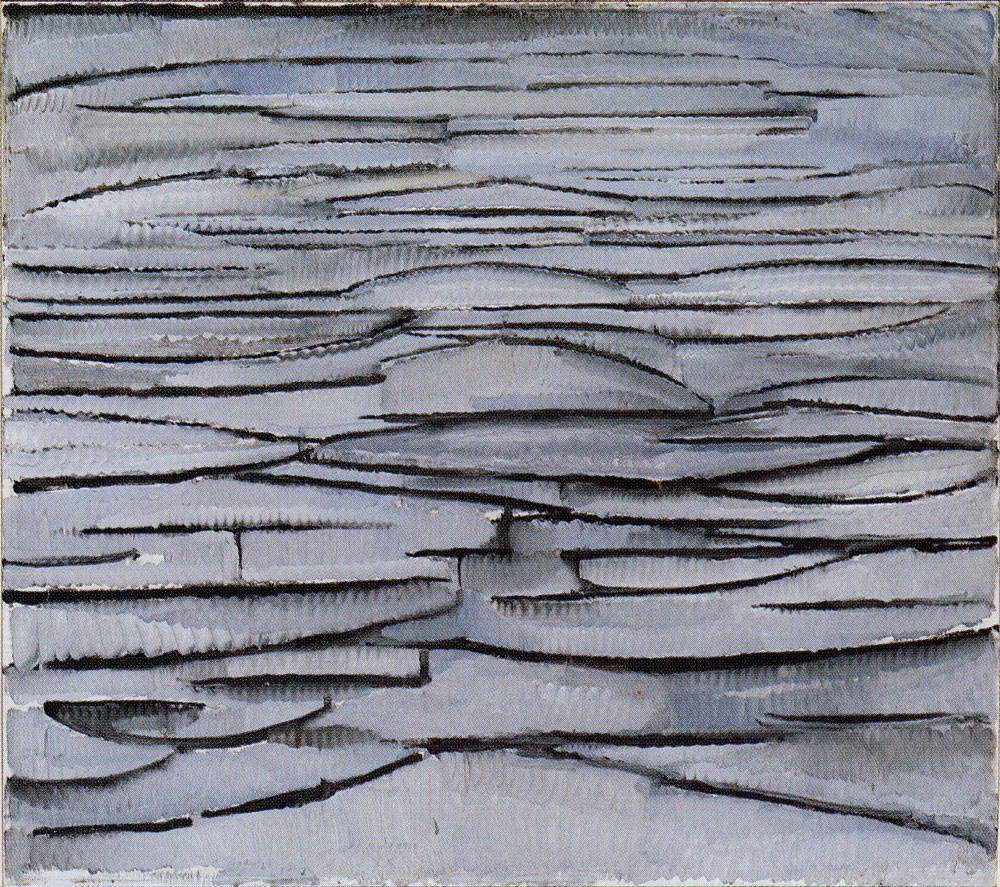

Mondrian himself was not unaware of the fact that others perceived him as a hermit, and on many occasions his own view comes to the surface in his letters. In August 1912, Mondrian stayed in the Dutch seaside town of Domburg, in the province of Zeeland, where he completed a few of the paintings he would send to the second Moderne Kunst Kring exhibition in October, including Paysage [B16] and The Sea [B17] (fig. 2). From Zeeland Mondrian returned to Paris. He then wrote a letter to his colleague and friend Mies Elout-Drabbe in Domburg, dated 23 September 1912, describing his experience: ‘I’m constantly being pushed towards the spiritual, even outside myself. I’m living here like a hermit again, and yet I only half want that!’ Arguably, Mondrian is describing his life in Paris, where he apparently had fewer social contacts than in the Netherlands. His ‘only half-wanting’ of this solitude indicates an ambivalence in Mondrian’s personality: on the one hand he was in need of social contact, on the other he required periodical seclusion in order to move forward in his art. In a later letter to Willy Wentholt in 1919, he wrote that ‘what I wanted so badly at first was to join in, in all kinds of ways’, referring to social events he would have liked to attend, or stronger human connections he would like to have forged.

Mondrian’s letter to Lodewijk Schelfhout

A similar case of Mondrian’s ambivalent attitude can be inferred from an exchange of letters in 1914 with Lodewijk Schelfhout, a Dutch painter and friend, who had just moved back from Paris to the Netherlands. Schelfhout had written that he rejected living like a hermit, unlike Mondrian. Mondrian replied: ‘As my actions in many respects have proven, I am not a hermit by profession either and I too, like you, must participate fully in life.’ Schelfhout’s remark clearly shows that the perception of Mondrian as solitary and anti-social is not simply the result of posthumous mythification, but rather an observation rooted in Mondrian’s lifetime. The artist’s wish to reject this idea by confessing he is not ‘a hermit by profession’ indicates that, although Mondrian is familiar with the label he has been given, he does not go along with it.

Self-fashioning

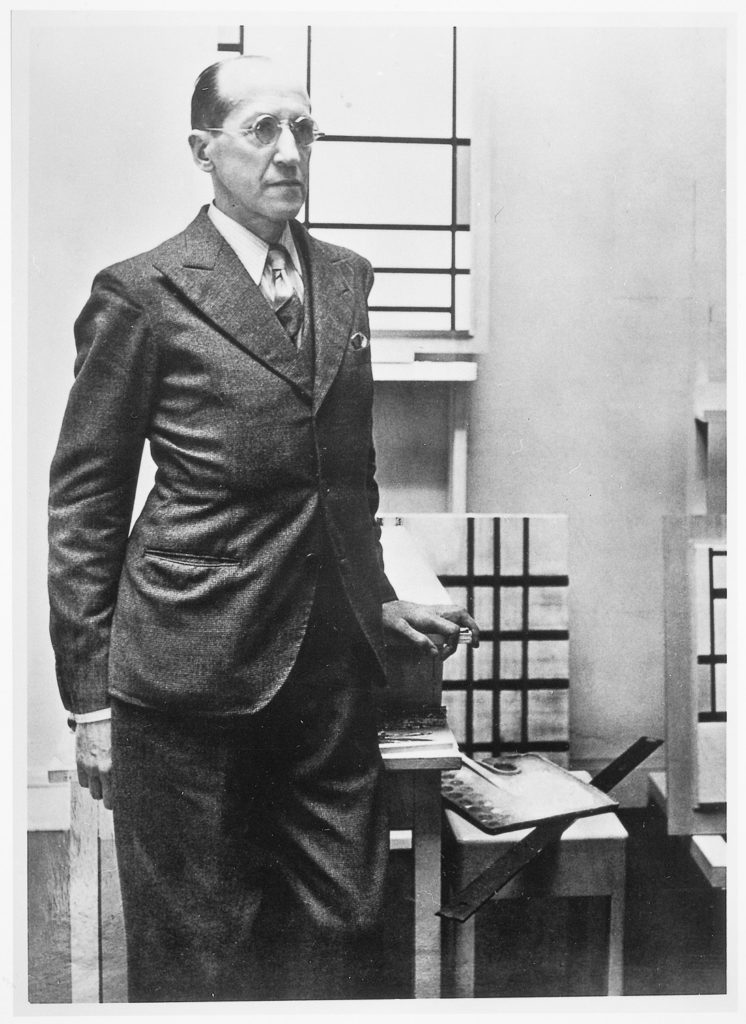

The desire to reject this idea might seem at first glance to clash with some of the posed photographs of Mondrian in his studio taken in his later years. However, while such photographs in many respects show his stiff and formal posture, Mondrian was well aware that the photos were sometimes intended for publication. For instance, in the case of the shoot for the catalogue of the exhibition Origines et développement de l’art international indépendant, in the Musée du Jeu de Paume in Paris, Mondrian is posing rigidly and unnaturally, presenting himself as a serious and somewhat detached person. (fig. 3) However, if we take a look at some of the more intimate photographs of Mondrian it becomes apparent that he enjoys being in the company of others and belonged to numerous groups of friends (fig. 1). In fact, he would keep in contact with a large circle of people throughout life, and extended his network of connections in every city he lived. While his letters have a more personal character and show him rejecting the idea of being a hermit, photographs showing Mondrian in his studio published in journals and newspapers from 1930 onwards seem to nourish the public myth of an aloof figure, providing a contrast to Mondrian’s private view of eremitism. One gets the impression that Mondrian deliberately used his appearances in public to present a specific image of his artistic persona.

The artist vs the man?

It is the public image of Mondrian that has allowed interpretations and myths about Mondrian’s supposed eremitism to arise through the years. The personal recollections of Mondrian’s closest friends, however, strongly contradict this myth. In her memoir Confessions of an art addict, for example, Peggy Guggenheim writes: ‘Another day Piet Mondrian, […] walked into Guggenheim Jeune, and instead of talking about art, asked me if I could recommend a night club. As he was sixty-six years old, I was rather surprised, but when I danced with him, I realized how he could still enjoy himself so much. He was a very fine dancer […]’. Guggenheim clearly portrays Mondrian as a social man, and not at all as a hermit seeking nothing but solitude.

The end of the myth?

A survey of all surviving portrait and studio photographs showing Mondrian is to appear later this year. This study, entitled Meeting Mondrian. The Complete Photographs, is the first lengthy publication that outlines how the myth of Mondrian was actually fuelled by the way the artist sought to represent himself in photography. By combining ‘official’ photographs, that were often clearly intended to contribute to Mondrian’s public image, with lesser-known photographs from Mondrian’s more private circle, the book offers insight into how Mondrian was portrayed. Readers who are attached to myths will find all of the photographs that support the cliché view of Mondrian; however, Meeting Mondrian also includes plenty of images for those who can embrace a broader picture that is closer to the truth.

Clarissa Frascadore studies Art History at the University of Utrecht and was an intern with The Mondrian Papers between September 2021 and February 2022.