by Leo Jansen

There is a well-known saying, used all over the world: ‘l’histoire se répète’ – history repeats itself. It is typically uttered in times of unpleasant or even dramatic events. For example when an army brutally and senselessly invades another country in order to sow death and destruction. Wars are as old as humanity and citizens will always be forced to flee from danger. In the very worst case, taking action requires everything to be dropped and people simply abandon house and hearth. Those who, despite the threats, have time to plan their departure can later see how fortunate they were given the circumstances. Such was the case with Piet Mondrian: he fled Europe because he was one of those placed by the Nazis on their list of ‘Entartete Künstler’, degenerate artists. But he had time, as well as support. Mondrian’s estate includes documents that tell us about his flight from London to New York in 1940.

Previous events

The atmosphere in Europe was already depressed following the Wall Street Crash of October 1929, which brought a long and deep worldwide economic crisis. But it was the appointment of Adolf Hitler as Chancellor and the election victory of the NSDAP at the start of 1933 which truly darkened the future for many in Europe. For years German expansionism had been fermenting and people felt that war might come, was indeed inevitable – certainly with Germany’s arch rival, France, but the expectation was for war on a wider scale.

In 1937 Mondrian’s art, like that of many avant-garde contemporaries, was branded as ‘entartet’ by the Nazis, using a much-publicised travelling exhibition. In the event of a German occupation of Paris – a threat that was taken very seriously – there was a real chance of him being arrested. In September 1938 this was partly why he slipped over to London, helped by his English friends Ben and Winifred Nicholson, to a place which at that moment was still safe. The city suited him and, artistically speaking, he thrived there: under the influence of his new surroundings his work took him in different directions; he was welcomed by the small circle of abstract artists and he fell in with a number of important supporters of abstract art, including the American collector and gallery owner Peggy Guggenheim – who like him had fled from Paris –, as well as the art historian and critic Herbert Read, and the Belgian publisher/gallery owner E.L.T Mesens.

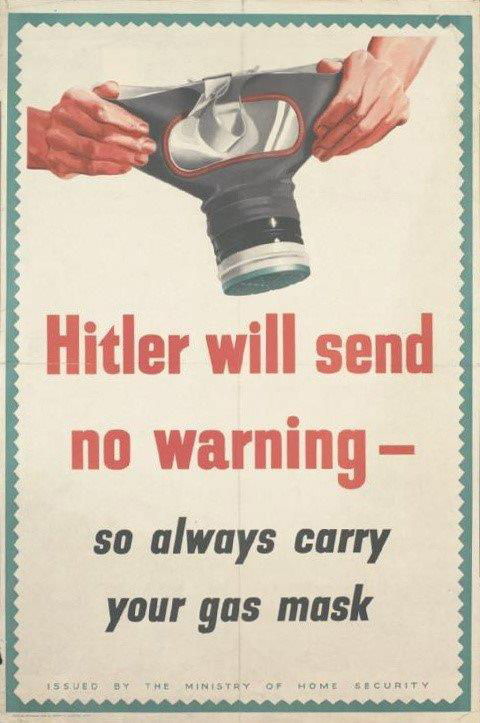

On 3 September 1939 England declared war on Germany. From that moment on, London became a target for bombardment. Quite soon some of Mondrians important friends, such as Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth (Mondrian was living in the same studio complex) and the couple Miriam and Naum Gabo, left the city for the country; Mondrian’s circle, made up of people who appreciated his art and were prepared to help him in a number of practical ways, was suddenly reduced radically. Government rules meant he was required to carry a gas mask at all times, and once the bombing started in earnest in September 1940, he was forced to spend time in air-raid shelters (fig. 2). A bomb fell close to his studio and his blacked-out windows were shattered. By then Mondrian’s preparations for emigration to the United States were already well under way.

Paper trail

In order to travel to the US, Mondrian needed to obtain a visa from the American consulate in London. On 24 June 1940, in response to his application, the American Consul General John G. Erhardt informed him that the consulate would give him an interview – with no guarantee of a positive outcome – ‘if you first will submit by mail to this office for preliminary inspection all available financial evidence regarding any income and resources of your own, and affidavits of support from your relatives in the United States together with corroborative evidence of their incomes and resources.’ Four days later Mondrian replied to say that he had forwarded the apparently essential ‘form B’ to his American guarantor to obtain the requested information. He also sent in twelve letters which he had received over the previous ten years from several sources, from which it emerges that his work had been bought by museums; Harry Holtzman had already invited him to come to America several times, would pay for his journey and promised to buy work by Mondrian; that his work was being sold as well as exhibited in New York; and that the American School of Design in Chicago (through his friend László Moholy-Nagy) and Columbia University in New York (through his friend Frederick Kiesler) had invited him to come and teach. He also mentions that he had £100 in cash and that a few of his works were already placed on consignment in the US – this last was naturally to demonstrate that he could expect an income from the sale of such works. Finally: ‘I can give legal references to my respectability from persons in this country if desired, and shall be pleased to hear further in due course.’

The letter was written in faultless English and furthermore it was typed. It seems it was Mondrian’s friend, the lawyer Robert Ody, who composed and typed up the letter. Ody arranged to provide one of the ‘legal references’ himself, typed on headed paper from his own office, Ody & Wilmot Solicitors. The letter is dated 6 July 1940 and addressed ‘To Whom it may Concern’: ‘I have been personally acquainted with Mr. Piet Mondriaan of 60 Parkhill Road Hampstead for some two years, but have known of him through mutual friends for several years longer. He is a well known Artist (Painter), and from my knowledge of him and his affairs I can testify him to be a thoroughly honest and respectable and responsible person who would make a desirable citizen in any country he might reside in. [sign.] R.H.M Ody’. Thanks to this and other references from his friends, Mondrian received his visa.

But there were further obstacles to overcome. To begin with, in wartime you could not simply leave the country. Several forms for travellers have survived listing the rules for taking money out of the country. A flyer from the Passport and Permit Office lists restrictions on the export of currency and states that a passport would only be issued if a confirmed booking from a shipping company could be shown (this passage was underlined by Mondrian). There are also several records of money sent by Holtzman; in August 1940 Mondrian received $250 from his friend, which according to the receipt he exchanged for about £61 (fig. 3). He would have used this to pay for the crossing, and possibly also for his stay at the Ormonde Hotel in Hampstead during the eight days immediately before departure on 20 September. The hotel invoice has survived, and thanks to this we know that the bill came to 2 pounds, 3 shillings and ninepence. As the destructive and terrifyning Blitz of London began on 7 September, Mondrian mainly spent these days in the hotel’s air-raid shelter.

The journey

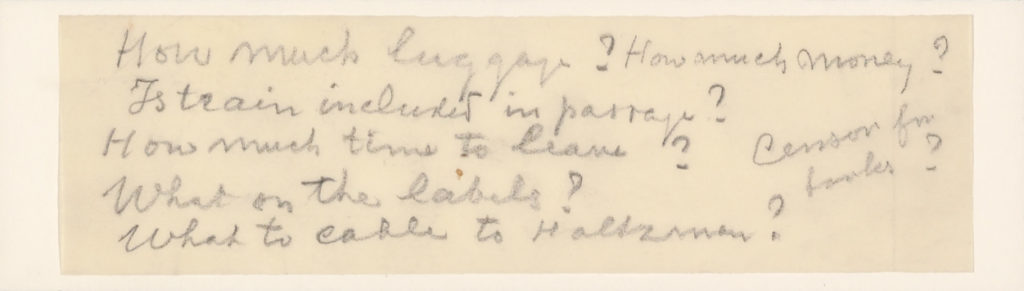

Then the journey itself: there were limits to the luggage that could be taken along. What was allowed and what restrictions applied? These are questions which Mondrian himself must have asked, probably at the famous travel agent’s, Thomas Cook (fig. 1): ‘How much luggage? How much money? / Is train [from London to the port of Liverpool] included in passage? / How much time to leave? / What on the labels? / What to cable to Holtzman?’ And as a final concern, appropriate for wartime: ‘Censor for books?’ Another sheet gives an indication of what Mondrian actually took along in a trunk and a suitcase. (fig. 4) He sent his paintings separately in advance.

Robert Ody took Mondrian by car from London to Liverpool, from where the SS Samaria would take him and other refugees to safer shores. The sailing, planned for 21 September, was delayed by two days because of German bombing of Liverpool. On 3 October 1940 Mondrian set foot on land in New York, following a crossing which had been an ordeal for him. But he was safe. Harry Holtzman was waiting for him.

Mondrian had several good years ahead of him. Not everyone forced to leave their country can expect such a good experience.