by Leo Jansen

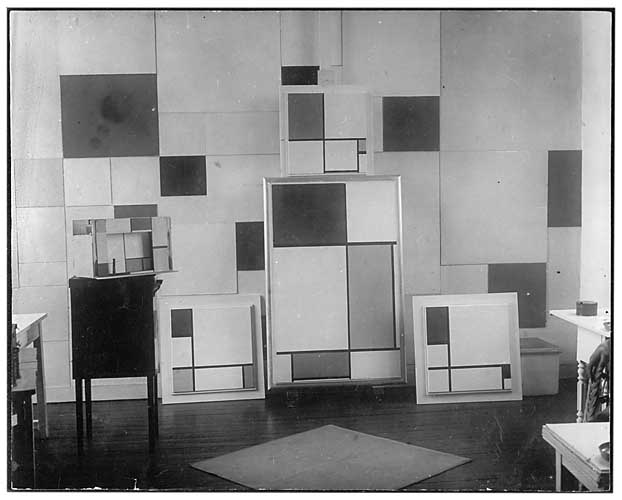

Every now and then something unexpected comes to light at an auction. In June 2018 three black-and-white photographs appeared in a sale in Cologne, showing close-ups of a maquette for a stage set designed by Piet Mondrian in 1926. It was long known that Mondrian had made the model; it appears, for example, in the photo of his studio shown above, where it can be seen standing on the black cabinet to the left. Moreover, several copies of the close-up photographs were in circulation and indeed reproduced in magazines in Mondrian’s lifetime. What makes the Cologne photographs unique is not so much the images themselves, but rather what can be seen on the back of one of them: a previously unknown sketch by Mondrian, in which he indicated the intended colours for the stage set.

Mondrian and theatre?

Mondrian considered his aesthetic principles – which he referred to as De Nieuwe Beelding or neo-plasticism – to be relevant not just to painting but also to the space around us. Indeed, he published several articles about this. His Paris studios were artistic laboratories where he experimented with fixing coloured rectangles to the white-washed walls, and painting his furniture white, black or in primary colours. His studio at 26 rue du Départ, where he lived and worked from 1921 to 1936, has become particularly famous for this.

In the late spring of 1926 the Belgian artist and writer Michel Seuphor (1901-1999) paid a visit to Mondrian who was a close friend. Seuphor had just returned from a tour of Europe lasting several months. He had stopped off in Rome to see the Italian futurist Giacomo Balla, and in a single night Seuphor had written an absurdist play, titled L’éphémère est éternel (the ephemeral is eternal). It was intended as a piece of anti-theatre: Seuphor had broken radically with the conventions and rules of traditional drama. This appealed greatly to Mondrian and, according to the Belgian artist’s memoirs, Mondrian surprised him a few days later with the maquette of a stage set for the play.

Three acts, three photographs

Mondrian constructed the maquette out of plain cardboard, wooden battens, glue and nails, with strips of canvas at the sides. The set is a blend of neo-plastic architecture and painting, and it occupies a special place in Mondrian’s oeuvre. It is furthermore the first and only time that the artist is known to have turned his hand to practical stage design.

Since the play consisted of three acts, Mondrian designed three different backdrops, which slotted into the proscenium surrounding the stage, and could be lowered or raised. On the stage he placed a wooden figure, with nails for arms, to give an impression of the intended scale and proportions. Judging from photographs that show the model in Mondrian’s studio, including the one reproduced at the top of this post, the dimensions of the model must have been roughly 30 x 44 x 14 cm. The fact that Mondrian placed the maquette on display when his studio was photographed shows that he regarded the piece as a serious example of his work as an artist.

Shortly after completing the model Mondrian received a visit from the young Hungarian photographer André Kertész, who is now famous and had been introduced to him by Seuphor. In addition to a series of beautiful, carefully staged photographs of Mondrian in his studio, Kertész made the three informal snapshots of the stage design maquette which were recently auctioned. The photograph reproduced here shows the backdrop for the second act of the play.

Sketch discovered on the reverse of the photograph

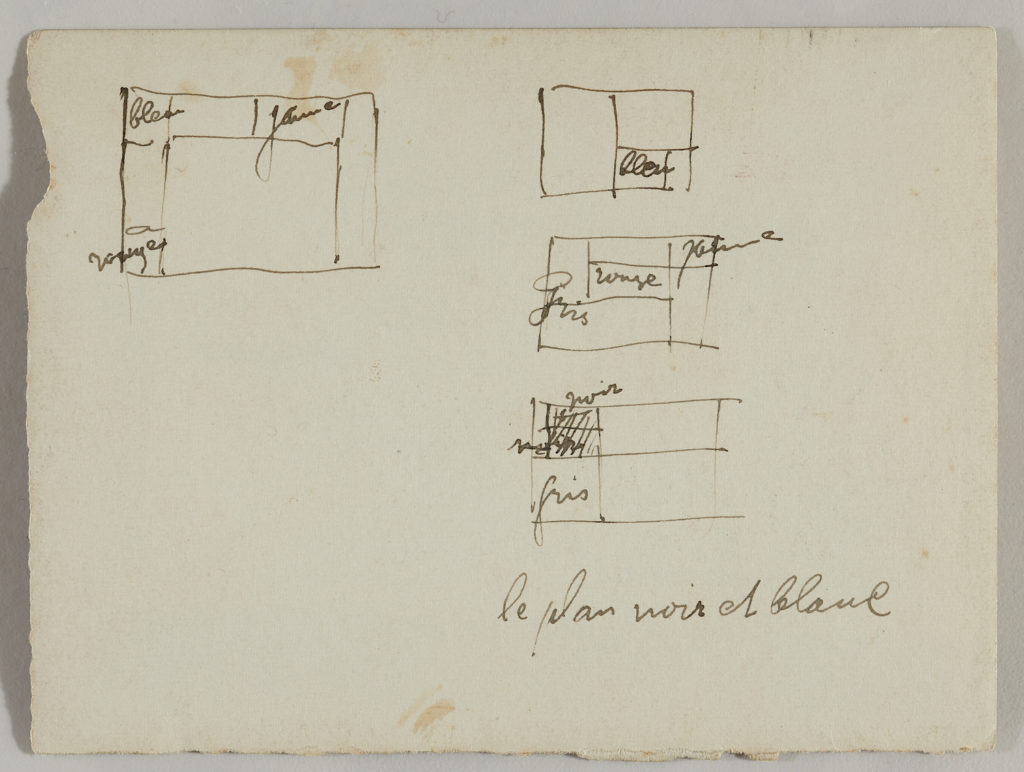

If we now take a look at the sketch that was discovered, we can see, top left, the proscenium, with colour indications: ‘bleu’, ‘jaune’ and ‘rouge’ (blue, yellow and red). Shown to the right, one above the other, are the three backdrops for the different acts, again with colour instructions: the uppermost is labelled ‘bleu’; the one underneath, ‘jaune’, ‘rouge’ and ‘Gris’ (yellow, red and grey), and the one at the bottom ‘gris’ and ‘noir’ (black; it looks as though Mondrian first scribbled ‘Gris’ in the panel, then decided to replace this, writing ‘noir’ to the left, eventually putting the word in again above). There are interesting differences between sketch and model. The sketched proscenium does not show the horizontal line on the right-hand section, and a horizontal line is missing top left in the backdrop for the second act. The note at the bottom, ‘le plan noir et blanc’ (black and white plane), seems to refer to the stage floor. The sketch includes no instructions for the side walls.

Reconstruction of the maquette

The original model was lost sometime after 1935, but a reconstruction was produced by the Van Abbemuseum for the 1964 exhibition Beeldend Experiment op de Planken (Visual Experiment on Stage). Only black-and-white photos of the original model survive, so Seuphor was called in to help reconstruct the colour scheme. The result can be seen in the photograph below:

Seuphor’s recollections almost 40 years later seem to correspond quite closely to Mondrian’s sketch, but – leaving aside the fact that the reconstruction is larger in scale than the original model – a number of striking differences can be observed. The photograph shows the reconstruction with the backdrop for the second act; according to Mondrian’s annotations, the upper-right panel ought to have been yellow and there is no sign of the ‘Gris’ specified bottom left. In addition, while the sketch does not indicate grey as a colour to be used for the proscenium, grey certainly was included in the reconstruction, using two different shades. Seuphor also chose yellow for the central panel at the bottom of the backdrop for the first act, while the sketch indicates ‘bleu’. All in all, Seuphor seems to have taken quite a few liberties. Possibly his memory had become unreliable; it is known that in later years he gave several different versions of anecdotes from his past. The recently rediscovered sketch provides important new insights that would certainly justify making a new reconstruction of Mondrian’s model.

The full article ‘The colour of black-and-white. An unknown sketch of a well-known set design’ by Wietse Coppes and Leo Jansen appeared in S. van Faassen et al (eds), Dutch Connections. Essays on international relationships in architectural history in honour of Herman van Bergeijk, Delft 2020, pp. 79-92. The open access publication is also available online: https://books.bk.tudelft.nl/index.php/press/catalog/book/780.